Content table

Trying to conceive can be an emotional rollercoaster. Defects in the luteal phase can create frustrating problems with conception. Here’s your guide to luteal phase defects.

You may have never heard of luteal phase defects, but they can cause big problems for women who are trying to conceive.

They’re essentially a problem with the ovulation cycle. The hormones that are supposed to help support fertilization and implantation are too low.

Luteal phase defects can make it harder for women to get pregnant. They can also cause losses in the early stages of pregnancy. Let’s talk about how defects in the luteal phase cause these problems.

What is the luteal phase?

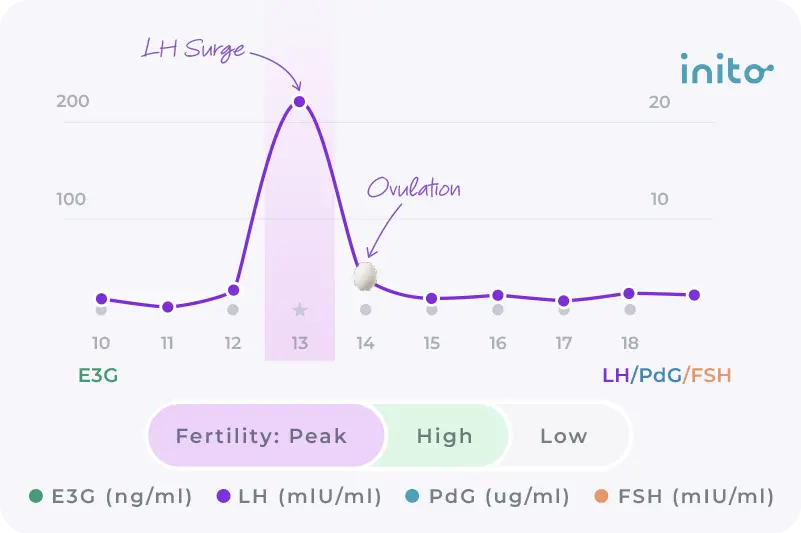

The luteal phase is the time occurring between ovulation and your next period. The average luteal phase is two weeks long. It begins after your ovary releases an egg and lasts until you get your next period.

Let’s have a quick recap of the fertility cycle. An average fertility cycle lasts anywhere between 21-35 days.

Here’s what an average woman’s monthly cycle looks like:

- Menstruation begins on the first day of your period, as your body sheds the uterine lining. Your period can last for two to eight days.

- The follicular phase is when a follicle containing an egg matures inside the ovary. This can take about 17 days on average.

- Ovulation happens around 12-14 days before your next cycle. The follicle releases an egg into the fallopian tube, where it can be fertilized marking your fertile window.

- The luteal phase is between ovulation and your next period. This phase is critical. In these 14 days, your body gets ready for a potential pregnancy.

Fertility hormones in the luteal phase help your body to prepare for a possible pregnancy.

Estrogen helps tell the uterine lining to thicken for pregnancy throughout the cycle.

During the luteal phase, the remnants of the ruptured follicle (aka the corpus luteum) secretes progesterone, which is a hormone that prepares your body for pregnancy. It helps thicken the uterine lining and makes the uterus a comfortable home for the developing baby.

Let us explore the role of this hormone during this particular phase of your cycle.

Progesterone and the luteal phase

Progesterone is tightly linked with the luteal phase. So much so that some practitioners use the terms “progesterone deficiency” and “luteal phase defect” interchangeably.

But where is all this progesterone coming from in the luteal phase?

You may know that the follicle is where an egg matures before release. But did you know that the follicle’s job isn’t done after ovulation?

After releasing an egg, the ruptured follicle becomes the corpus luteum. This structure produces progesterone in the luteal phase.

In the luteal phase, progesterone from the corpus luteum is responsible for:

- Preparing the uterus for implantation.

- Thickening the inner lining of the uterus so that it can nourish the embryo.

- Thickening the cervical mucus so that bacteria can’t get into the uterus.

- Causing a slight rise in body temperature.

The luteal phase has two outcomes:

- If an egg is not fertilized or implantation doesn’t happen, the corpus luteum disintegrates around 9-11 DPO. The hormones estrogen and progesterone decrease and your period begins.

- If an egg is fertilized and implants into the uterine wall, a structure called the placenta is formed. The placenta starts producing the pregnancy hormone – human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).

This hormone tells the corpus luteum to stick around so that it can keep releasing progesterone. Instead of your period, you’ll see a rise in hCG, which could ultimately result in a Big Fat Positive (BFP) pregnancy test.

What is a luteal phase defect?

A luteal phase defect means that the body has trouble preparing for pregnancy after ovulation. This is either linked to a problem with low progesterone or to a problem with responding to progesterone.

Read More: Low progesterone: All you need to know

Let’s break down how a luteal phase defect occurs, bit by bit.

Progesterone from the corpus luteum tells the uterus to get ready for pregnancy in the luteal phase. The uterus responds by thickening the uterine lining so that an egg can attach there.

But without progesterone, the changes that are supposed to happen in the luteal phase cannot occur.

Alternatively, progesterone can be high, but the body may not be responding to it. For either reason, the result is that the uterus isn’t preparing for pregnancy the way it should.

The uterine lining is supposed to be thickening, but it doesn’t. The uterus should be getting ready for implantation, but it doesn’t. And the cervical mucus that’s supposed to thicken to protect the uterus may stay thin.

In these conditions, pregnancy is much less likely to be successful. Implantation can’t happen, and the placenta can’t develop.

Luteal phase defects are often a cause of recurrent pregnancy loss. They can also lead to infertility and subfertility.

That’s why luteal phase defects can be frustrating for women trying to conceive. For more information on miscarriage click here.

What causes luteal phase defects?

Scientists think that problems with the corpus luteum cause low progesterone in the luteal phase. Or it could also be a problem with how the body responds to high progesterone levels.

Beyond that, research isn’t fully developed on why some women have problems in the luteal phase while others don’t. But some diseases and body changes can be associated with luteal phase defects.

Here are a few of them:

- Eating disorders

- Exercising excessively

- Stress

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

- Endometriosis

- Advanced maternal age

- Thyroid problems

- Using assisted reproductive technology

- Smoking

Symptoms of luteal phase defects

Luteal phase defects are linked with these key symptoms:

- A shorter luteal phase and a shorter menstrual cycle in general

- Abnormal bleeding throughout the menstrual cycle

- Lighter periods

- Infertility

- Prior miscarriages

Do I have a luteal phase defect?

Luteal phase defects aren’t easy to diagnose. You won’t know if you have a luteal phase defect until you speak with your gynecologist or fertility specialist. They’ll likely want to do tests to see if they can find a different diagnosis first.

Even experts don’t have a consensus on diagnosing luteal phase defects. There isn’t one test that can determine luteal phase defect or infertility in general.

Here are a few ways your care provider may determine your diagnosis:

- Tracking your menstrual cycle: If your luteal phase is consistently less than nine days, this may be a sign of dysfunction.

- Tracking progesterone in the luteal phase: Repeated testing can help your provider see if your progesterone levels are lower than expected.

Learn More : PdG Test: Key Things To Know About Progesterone Tests - Endometrial biopsy: Getting a sample of your uterine lining may help your provider see if there are any abnormalities.

Luteal Phase Defects and Pregnancy

Defects in the luteal phase can make it hard to get pregnant and stay pregnant. But it’s still very possible to have a baby, even if you experience a shorter luteal phase.

Many women may have a few shorter luteal phases, but they return to a better rhythm with time.

In one 2017 study, shorter luteal phases had a short-term negative effect on fertility. Women with shorter luteal phases were less likely to get pregnant in that cycle. But over a year, women who experienced a short luteal phase were just as likely to get pregnant as other women.

Shorter luteal phases are more common than previously thought. In the same study, 18% of women over 30 experienced at least one shortened luteal phase. Only 3% of women had shortened luteal phases that recurred more than once.

It’s uncommon to have repeated luteal phase defects. So even if you have one shorter than usual, you’ll probably return to your normal cycle in the next month.

Tracking your luteal phase

A luteal phase of less than nine days may signify a luteal phase defect. Another sign is low progesterone levels. Both will make it hard to get pregnant in this cycle.

Luteal phase defects and PCOS

Experts believe that some of the fertility problems associated with PCOS may be linked to the luteal phase. The two issues are independent of each other, but they share some characteristics.

Women with PCOS may be more likely to have shorter luteal phases and more irregular cycles.

Both PCOS and luteal phase defects are associated with progesterone issues. Low progesterone levels in PCOS and luteal phase defects contribute to early pregnancy loss.

Luteal phase defects and PCOS are also associated with high insulin levels in the blood. Insulin and progesterone have an inverse relationship. When insulin is high, progesterone is low.

PCOS has more specific challenges and is far more common than luteal phase defects. See our complete guide on getting pregnant with PCOS for more information.

To get pregnant with PCOS and luteal phase defects, your gynecologist will prescribe medicines to reduce the insulin levels and progesterone supplements to increase the progesterone levels.

How to fix luteal phase defects?

Some research has found that luteal phase defects could be associated with dietary imbalances.

This study found that the Mediterranean diet could positively affect fertility, specifically in the luteal phase. Increased fiber intake, as well as decreased inflammatory foods, helps regulate body systems.

The same study found that increasing iron and vegetable protein intake helped with luteal phase defects. Shellfish, spinach, and legumes are foods with good iron content. Vegetable proteins include tofu, lima beans, and green peas.

Dietary selenium was also associated with improved luteal phase defect. Some foods high in selenium include Brazil nuts, fish, and other lean meats.

If you’re noticing a shorter luteal phase, try adopting a Mediterranean diet rich in iron, vegetable proteins, and selenium. Besides being suitable for the luteal phase, these foods are also associated with cardiovascular benefits and weight loss.

Luteal phase defects treatment: Here’s what could help

Luteal phase defects aren’t generally a problem unless you’re trying to conceive. Having a few shortened luteal phases is also generally not a problem.

Even for women who have repeated luteal phase defects and are trying to get pregnant, there isn’t any immediate treatment.

Treatment measures start with treating associated problems, like thyroid disorders and smoking. Generally, your provider will want to rule out other strategies before recommending fertility treatments.

Some methods understood to help women with luteal phase defects get pregnant are:

- Ovarian stimulation: These medications cause the ovaries to release eggs. The idea is that the corpus luteum should secrete progesterone after ovulation. Yet this hasn’t been verified as a successful way to treat luteal phase defects.

- Progesterone supplementation: Instead of trying to make the body produce more progesterone, supplementation replaces it. Progesterone has been proven to help women with repeated miscarriages retain pregnancies. Yet much like ovarian stimulation, there isn’t hard evidence that progesterone can treat luteal phase defects.

Summary:

- Luteal phase defects mean problems with preparing for pregnancy after ovulation. There is typically an underlying problem with progesterone that causes them.

- We’re still not sure what causes some women to have problems in the luteal phase. But some research has shown that dietary changes could help women achieve more regular luteal phases.

- Luteal phase defects are associated with shorter cycle length, spotting between periods, and problems with conceiving.

- There isn’t one test to tell if you have a luteal phase defect.

- Trying a Mediterranean diet may be one way to fix a luteal phase defect.

- Luteal phase defects have no single treatment method. Your provider will probably try to treat associated disorders before using fertility treatments.

Was this article helpful?

- Andrews, M. A., Schliep, K. C., Wactawski-Wende, J., Stanford, J. B., Zarek, S. M., Radin, R. G., Sjaarda, L. A., Perkins, N. J., Kalwerisky, R. A., Hammoud, A. O., & Mumford, S. L. (2015). Dietary factors and luteal phase deficiency in healthy eumenorrheic women. Human reproduction (Oxford, England), 30(8), 1942–1951. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev133

- Bull, J.R., Rowland, S.P., Scherwitzl, E.B. et al. Real-world menstrual cycle characteristics of more than 600,000 menstrual cycles. npj Digit. Med. 2, 83 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0152-7

- Crawford, N. M., Pritchard, D. A., Herring, A. H., & Steiner, A. Z. (2017). Prospective evaluation of luteal phase length and natural fertility. Fertility and sterility, 107(3), 749–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.11.022

- Diagnosis and treatment of luteal phase deficiency: A committee opinion. (2021). Fertility and Sterility, 115(6), 1416–1423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.02.010

- Knudtson, J., & McLaughlin, J. E. (2022, March 30). Menstrual cycle – women’s health issues. Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/women-s-health-issues/biology-of-the-female-reproductive-system/menstrual-cycle

- Meenakumari, K. J., Agarwal, S., Krishna, A., & Pandey, L. K. (2004). Effects of metformin treatment on luteal phase progesterone concentration in polycystic ovary syndrome. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 37(11), 1637–1644. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-879×2004001100007

- Schliep, K. C., Mumford, S. L., Hammoud, A. O., Stanford, J. B., Kissell, K. A., Sjaarda, L. A., Perkins, N. J., Ahrens, K. A., Wactawski-Wende, J., Mendola, P., & Schisterman, E. F. (2014). Luteal phase deficiency in regularly menstruating women: prevalence and overlap in identification based on clinical and biochemical diagnostic criteria. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 99(6), E1007–E1014. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-3534